Still Here

A year after the murder of George Floyd, VICE reached out to activists, politicians, artists, and others we’ve spoken to in the past. We asked them about their memories of the last year, what’s changed during that time, what they’ve achieved, and what they expect from the movement for racial justice going forward.

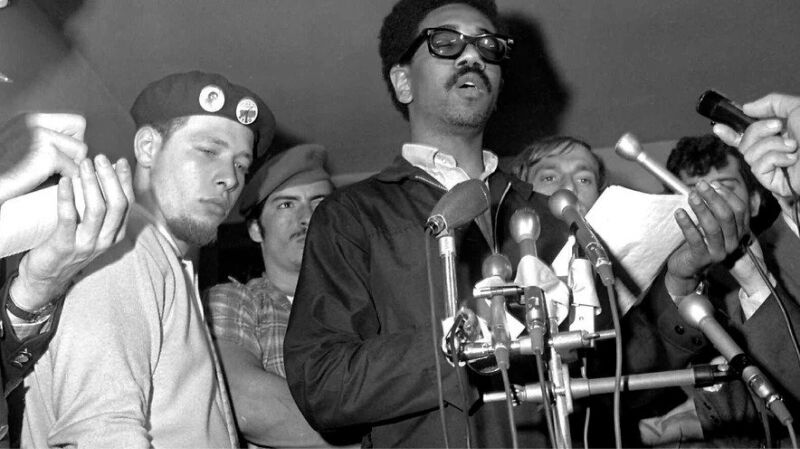

Rep. Bobby Rush

“I just can’t ever forget the evil that was in the eyes of Derek Chauvin. I can’t forget the total racist arrogance that he had. He held his hand in his pocket, seeming to say that he was the most powerful, that he was a god, and that this man who was pleading for his mother was subhuman. That memory is etched into my soul, consciousness, because in that one instant I traveled back hundreds of years to slave ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean and the thousands of slaves in the belly of the slave ship. I don’t think I’ll ever get that image out of my system.”

Carroll Fife

“I won’t forget how depressed I was after I heard the verdict. And it was strange because I had not expected to be so emotional about a verdict that I figured would happen. I thought, ‘If they let him get off, this whole place will implode. Cities will implode internationally.’ I just didn’t think that was a risk that folks wanted to take. So I expected the results. I just was so—I couldn’t function for the rest of the day. I’m like, Oh, my god, I have these community meetings and council things that I have to do, and I’m having a hard time getting through the fact that I think it was like the Obama effect—that once this happens, people are going to be like, ‘There is justice in the world.’ And it is not. It’s not. We’re not even close.”

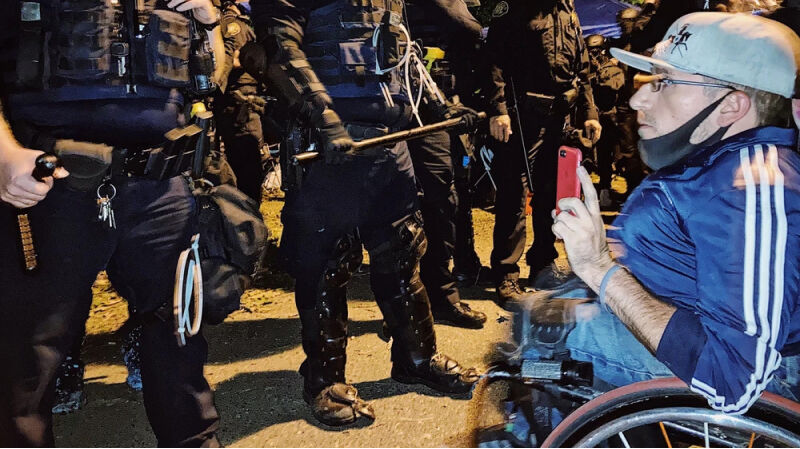

Chris Wise

“Really, all of the things that come to mind when I think about the year 2020 are all individual patient stories. I don’t think I’ve ever seen that much condensed police brutality in my life, so the things that I remember have all just been injuries, and, you know, what I had to do in the moment. Because people who go to protests against police brutality or for Black lives or for whatever motivated them to come out and show support, don’t expect to be brutally assaulted by the police—not just in the sense of general assault but being assaulted with weapons.”

Dr. Steven McDonald

“The moment I remember most vividly but also is probably the least interesting is going into my bodega the week of George Floyd’s murder and confronting this woman in the bodega who did not have a mask on and saying, ‘I’m a physician, and I’m a little bit traumatized by you being in here, and you’re also putting all these people at risk who are essential workers.’ And she, without missing a beat, just turned around and said, ‘You fucking nigger doctor.’ And I… That seared in my memory that this is thought to be a problem in the United States writ large, less so in New York City.”

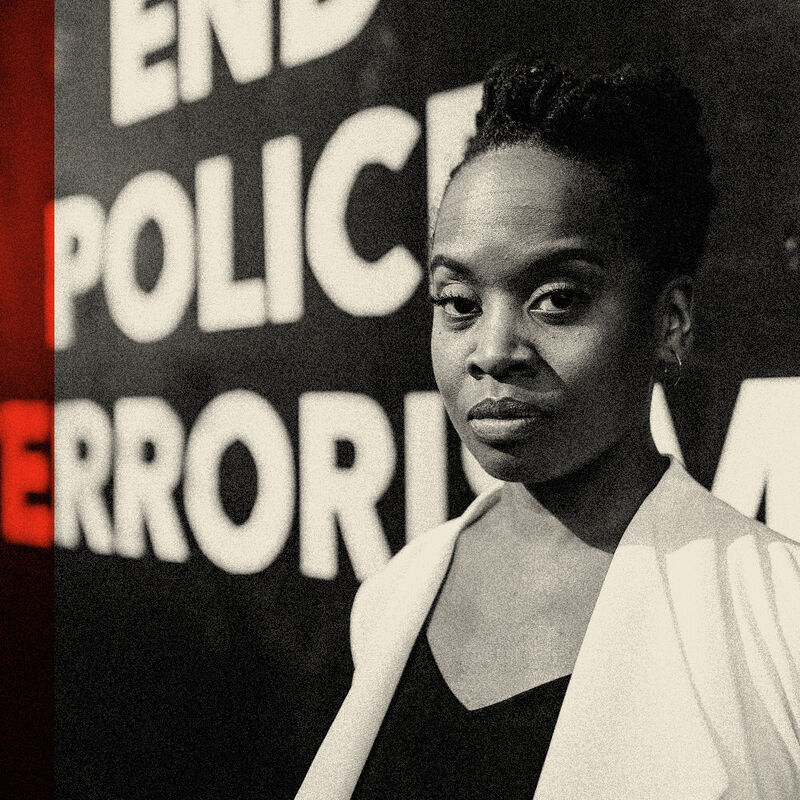

Sandy Hudson

“I was in Portland during the end of the summer of 2020, and by that point they had been protesting for over 100 days. Portland was really vivid because we came face-to-face with a very hostile police apparatus. People were like standing around gathering, just welcoming one another. People had this truck where they were trying to feed one another, and then the police just started throwing tear gas and everyone just started running and screaming. There was probably enough police there for every single human. They were attacking journalists. It was like, what the fuck is going on? Coming face-to-face with what it means to stand and say in solidarity with Black folks, ‘Yes, this must end, yes the violence has to stop, yes we need to defund the police,’ and seeing how much of a threat the state determined that was, to the point where they were really willing to attack people who weren’t doing anything at all. It almost felt like maybe they thought it was a game, because there was no rhyme or reason to it. It’s not like there was instructions, like, ‘This is an illegal gathering. Please disperse and go to your homes, and if you don’t, this will happen.’ Things just started happening. You would hear the projectiles, and people were sharing with each other helmets, like, ‘Put these on and let’s run.’ They were just chasing us throughout the city. Just terrorizing people.”

Rachel Bean

“Much of the last year has been a blur, and there have been many vivid moments, but I think the Thursday night of the uprising, watching the Minneapolis Police 3rd Precinct burn, was a big one. I felt a lot of possibility in that moment. The people were in the streets, everything was on fire, and it seemed like things might actually change. I also felt a lot of possibility in the early morning of Sunday, May 31, after we were able to secure the hotel and get unsheltered people into hotel rooms that first night.”

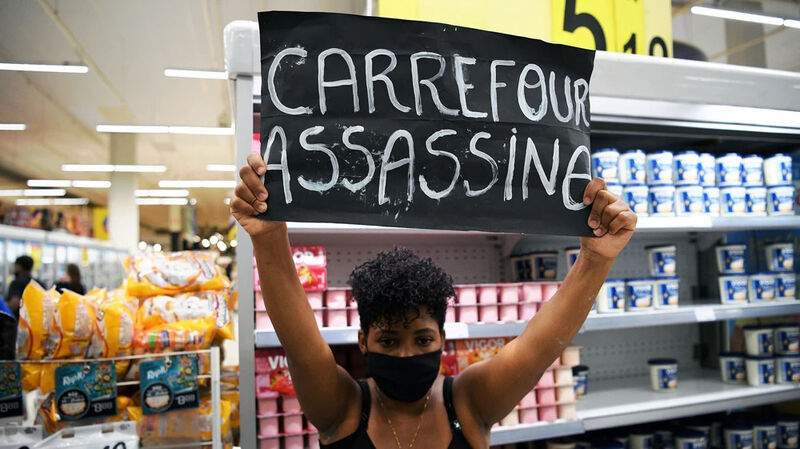

Bruno Sousa

“After the shock of George Floyd’s death, it was a very powerful movement because we were in the peak of the pandemic. The majority of people were very frightened of leaving home due to the virus. But even still, we felt obliged to go out. We thought, ‘We’ll die from the virus, or we’ll die from a gunshot.’ So we went to the streets to protest. I think that was my most vivid memory, as it was global. It happened in the U.S., Brazil, and all over, because racism is present in the whole world.”

Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II

“When I was watching the trial, to finally see officers of the law, Black and white, who were willing to break the ‘blue code of silence’ and say, ‘We have to testify against this, because it’s wrong, and it’s actually an endangerment to those police who believe in the true protect and serving, and that unlawful policing is a threat to the whole society.’”

Dominique Walker

“I didn’t know that Derek Chauvin would actually be convicted. But I do understand that sometimes to uphold systems, they’ll sacrifice one of their own, like making an example out of him. But there’s nothing being done to the people who went to the Capitol or anything like that. And Black and brown bodies are still being disposed of in the street by police.”

Tyrek Morris

“I’ve become less tolerant of people’s bullshit and their perceptions on race and race relations. Generally, I’m less accepting of people’s ignorance. We’ve just had a whole summer teaching you about everything. I’m more clued up than I was before too.”

Rachel Bean

“There’s more anger now—I have yet to be able to wrap my head around the sheer volume of violence Chauvin inflicted on the city. But there’s also more visioning, more focus, and more possibility now. I contracted the coronavirus before Floyd was killed, but I got Long COVID after Floyd was murdered and eventually was forced to take a disability leave because I couldn’t keep up with my job after being so run-down. That space away from work, and the privilege to slow down for a while, really showed me how fucked we are in late capitalism and slow-rolling collapse. Being able to slow down allowed me to grieve for Floyd and others at George Floyd Square. Being able to slow down really allowed me to reconnect with my imagination, my creativity, and the possibilities for a more just future.”

Ben Crump

“I’ve often advocated, you have the two courts: the court of public opinion and a court of law. Oftentimes, I had been criticized for fighting in a court of public opinion, when you’re fighting for marginalized minorities in America. But it seems the success rate that we’ve been having with getting civil justice under the Seventh Amendment, more lawyers are starting to borrow from this Ben Crump model that says it’s not enough to fight in the court of law.

If you’re successful there, then, just then, maybe, you’ll get to fight in the court of law. There’s no guarantees. Eric Garner actually won in the court of public opinion but never got his due process; they never got their day in the court of law. So that’s what I mean when I say there’s a chance, but that’s the biggest change.”

Alan Duarte

“For me, the biggest impact and change was having to stop doing all the presidential sports activities at Abraco Campeão [Champion Hug], the organization I work for, which integrates martial arts with education, social and personal development, and adapting to online. Much of my work also turned to helping millions of families in my favela survive by distributing food baskets and hygiene kits. Lots of mothers lost their jobs, lots of providers of the family completely lost all of their income. Seven out of 10 favela residents lost their jobs due to the pandemic. We, as a social organization, based in the Complexo do Alemão favela in Rio de Janeiro, stepped in to support the families three weeks before the government offered any aid.”

Rachel Bean

“Suddenly everyone is talking about abolition and mutual aid. It felt like an explosion, or more aptly, a spring bloom of possibility and growth. The pandemic conditions, the Minneapolis Uprising, George Floyd Square, and the Sanctuary Hotel were all examples of how concepts of community care, mutual aid, and abolition all started materializing. Supplies and money were moved so swiftly. A volunteer fire brigade was created. Neighborhood watches were created. Networks to move money and goods were created and maintained. To me, the pandemic really revealed the ways the State will not and does not protect us and only the people protect each other. The police are an occupying force, not a public safety entity. The government did not provide enough financial relief to meet the scale of the pandemic crisis, so people had to start moving their money around, and fast.

In the first days of November 2020, I coordinated a fundraising push (something I call a ‘barnraiser’) to fundraise $20,000 for a Black woman to purchase the home she had been renting. Literally, in $5 and $10 increments, over Venmo and CashApp and PayPal, we raised $20,000 for a North Minneapolis resident to secure her home. That blew my mind, that we could move that much money in that informal of a way with no strings attached and actually get it done. That evening when we met the goal was an amazing moment of how much 2020 had shifted the way people engage each other. Raising that money, that quickly, in that way, mostly based on people trusting me at my word, demonstrated to me how much had changed.”

Jae Sterling

“There is this therapeutic thing now, where everyone is getting everything off our chest. They’re blasting it online and just really speaking from the heart—I’ve never seen people in Calgary speak up so much.”

Chris Wise

“A lot of my friends have told me that I’ve become a lot angrier, because I was previously known for having a fairly laissez-faire attitude toward a lot of things. I do talk about it more often. But it’s not like I’m angrier. This is a thing that I’ve always been angry about; I just wasn’t really talking about it. I’m a little bit more forceful in my opinions and my assertions, and I pick at it more often, if that makes sense. Like younger me probably would have let it go and just seem like, ‘You know what, it’s not worth it to talk about this. And current me is kind of like, ‘No, no, no. You know what? If you don’t want to talk about this today, fine. But we’re talking about it.’”

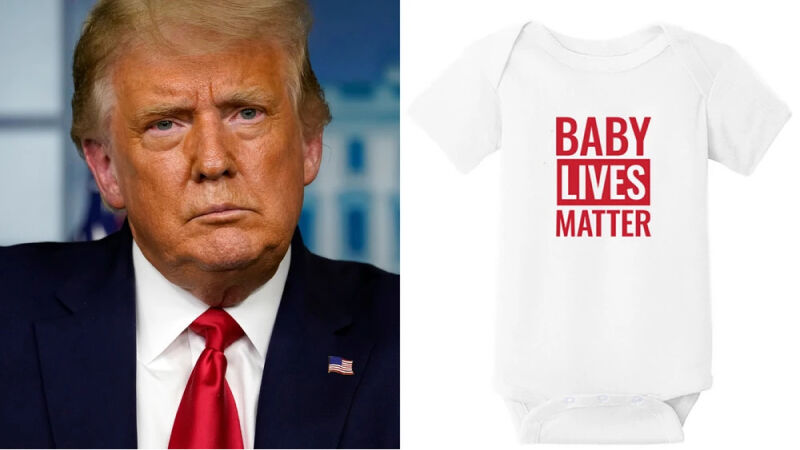

Renee Bracey Sherman

“I talk to children about it. I lived with my cousin and her family pretty much for the first year of the pandemic. So going through all of this, not just within our movement but then seeing the protests online and on television and talking to a 5-year-old about what’s going on, really helped me learn and grow in how I approach some of these things. I think we all sort of do this thing of like, ‘Oh, let’s just hope people do better.’ And sometimes I could feel myself allowing certain things to slide and to just suffer in silence about them. And that gets you exactly nowhere. It’s like, ‘OK, well, if I bring this up but in a nice way,’ people need to hear it directly because I’ve found that if I don’t talk about it directly, people don’t take me seriously.”

Nas

“Last summer was instrumental to a lot of us learning. There’s a perception that the people who were starting groups over the summer knew everything, but a lot of us are young people. For example, in our group, we had a 16-year-old calling to get people out of the police stations and making sure everyone was safe. So we’ve definitely changed the way we talk about it, because we’ve just seen now that policing itself can’t be reformed. The origins of policing are just inherently racist and classist. It’s not just police in America, France, or the UK. It’s not just police in the Western world that are oppressing people. So that was a real eye-opener. That made us students of abolition.”

Rep. Bobby Rush

“I think America has reached the point where it’s recognizing and has to address this ruthless violence of the police profession. We have to lift up, raise up, the police profession. It should be a highly paid, highly professional aspect of American life, and only the best of us should be able to carry out arrests and imprison and enforce the laws of our nation—only the best, not the worst.”

Carroll Fife

“This is Oakland, so we have some of the downest folks in the country, and they do not play. Even in the uprisings, people are starting to say, ‘You know if there’s a march and things get broken, that it’s the cops that are doing it.’ Because now, the marchers are so organized that they don’t mess Black, brown, or Asian businesses. I’m a city council member, so I drive around after a march, and I’m like, “No Black businesses were touched this time? That’s different. Only corporations? Huh. What’s happening right now?’ So it’s interesting to see that level of consciousness. Oakland is a special place.”

Rigodis Appling

“For white people, it is good for them to be there. But I do really think it is their job to talk to their family members and to talk to their people. Because there’s so much the Black community, Black women, Black voters, can do. We can educate. But it’s the white people’s job to educate their families, their aunt, their uncle who says the racial slurs at Christmas dinner. It’s your job to interfere, to correct, to educate all of these things. Obviously, racism is just rooted in ignorance, with people just not knowing people and going by stereotypes that we’re all just bombarded with daily through news, through everything. It’s not strange or weird or unusual for the majority of white people—the 55 percent or whatever that voted for Trump—to think the way that they do, given the history of America and the racism that is still very present today. When we talk about the criminal justice system, we can’t talk about this in some vacuum where, ‘If we just fix police…’ No, this is systemic. This is institutional. This is how we were all indoctrinated in America. Racism is in everything. So it is the job of every white person who is educated, who’s aware, and who has good information to not just spread that information but to interrupt and to correct their people and their direct families.”

Tyrek Morris

“I’ve noticed white people are a lot more performative with their views on Black Lives Matter. I’m going to make sure that you know I’m not racist. On TikTok they will put on a show to emphasize they aren’t singing [the N-word] in songs.”

Renee Bracey Sherman

“I think white people are starting to realize that actually they do need to go back and right the wrongs for the harms that they’ve caused. Some white folks have kind of absolved themselves and just decided to move forward without ever speaking to the people that they’ve harmed, and then others actually humble themselves and reach out to have conversations and say, ‘I know I have caused harm in the past. You’re under no obligation to respond to me, but I want you to know that I am doing a lot of soul-searching and work. I’d like the opportunity to apologize and hear out and have a conversation.’

I had, with a colleague in the movement, a really, really wonderful, healing conversation. She hurt me a lot in her white feminist behavior and racist behaviors at an organization that I worked at. Now, not all folks of color are gonna want to have that conversation with people. I certainly don’t want to have it with every single white person. I also respect all the folks of color who are like, ‘Yeah, I don’t want to hear it. I don’t want to hear any apology. Just do better. Don’t come apologize. You need to do better.’

I have told some white people in my life, like, ‘Be prepared that if you are going to make an apology, that someone is going to say, ‘No, I don’t want to hear shit from you.’ And be OK with that, because that’s their prerogative.”

Rep. Bobby Rush

“I don’t see a lot of truth and honesty about the willingness to sacrifice white privilege. I don’t see enough of that. We don’t have real, honest discussion around what does white privilege really mean? Does it mean the same thing to someone who lives in Manhattan as it means to a white person living in Mississippi? I don’t think it means the same thing”.

Chris Wise

“I feel like when it comes to race relations, there are a lot of white people who don’t notice those things because they have never been taught to and they don’t irritate them and they don’t actively affect their lives. But once you start teaching them, it kind of snowballs. For example, if you were to buy a Jeep Wrangler, you will see Jeep Wranglers on the road all the time. So I have noticed a lot more white people noticing what’s going on, but they don’t have a lifelong reaction to this, so they don’t know what to do. So sometimes they get like super, super over-the-top, like, ‘Hey, were you just doing this thing’ because they noticed, and they wanted to help, and that’s cool too. But sometimes it’s not enough. Sometimes they notice it and then they just kind of ignore it because it makes them super uncomfortable. And I understand that. But we’re living in a very uncomfortable time. You’re going to have to deal with it. Like, you can help or not help, but not helping is actively hurting.”

Rigodis Appling

“All the focus is on reforming police and police misconduct, but people fail to really acknowledge that prosecutors can hold police accountable. And I don’t just mean with a trial, like Chauvin’s trial or something. In not prosecuting the absolute bullshit that police bring up, they can just stop it right there. If a police officer commits any type of misconduct, the district attorney can say, ‘We are not prosecuting this person because of this misconduct.’ And that is a huge opportunity to reform police because if the prosecutor’s not prosecuting, the police will eventually stop bringing these, arresting, and whatnot. But instead the prosecutor fully supports, enables, and enhances the police department.”

Shalini Kantayya

“Our modern lives are lived online even moreso because of the pandemic. We need to have rights around this in a democracy. It’s imperative that we’re more cognizant of the invisible hand of power that these technologies have in shaping our lives, our perspectives, and our active opportunities. The cast of this film just made me see that there are other ways that artificial intelligence can work than this kind of surveillance capitalism model that we have come to see as the only way. The pandemic has only expanded the power of Big Tech and the disparate impacts in communities of color. Data rights are human rights. Algorithms, machine learning, artificial intelligence intersect with every civil right and freedom that we enjoy as people of a democracy. The new administration must pass policy that keeps pace with the way these technologies are eroding our civil rights.”

Tamara Toles O’Laughlin

“In climate, the biggest missed opportunity is the lack of action from some of the oldest organizations. In my view, they are taking no real, deep, or lasting stances against the insurrection as a culmination of a terror campaign against real people or showing how they have rooted out those forces in their own ranks.”

Gideon Oliver

“The City Council could have meaningfully defunded the New York City Police Department when the violence was on full display and at their doorstep, in a way that it isn’t all the time. And the city government didn’t. That’s one example of the many missed opportunities that I think New York City government had, to take what happened last summer and do something different. But that’s the first big one that jumps out at me. It was right there for them to do. And they refused.”

Aisha Thomas

“We don’t allow white children or children who are racialized as white to have this experience or have these discussions. When we miss these conversations, we miss the opportunity of cohesion and a sense of community and connection.”

Renee Bracey Sherman

“When workers spoke out about racism at our organizations in June, leadership within our movement was silent. It wasn’t until articles came out—in the Washington Post, BuzzFeed, Daily Beast, etc.—about racism within the movement, where workers had to go to the press, that’s when we got a response from some organizational leaders. Some still have not said anything, literally have not said anything about it.

To me, that signaled a level of deep disrespect for workers of color, for board members of color, for folks who’ve experienced racism in our movement. When we spoke about it, we were met with silence literally at the very same time that they’re issuing statements about, ‘We need to get racism out of everywhere in this country.’ Workers are like, ‘Cool, can we start in our office?’ And then they say nothing, internally and externally. That silence is a symptom of white feminism.

I personally have experience where I talked about the racism that I experienced, the racism and anti-Blackness that I witnessed. It definitely took well over a week and many colleagues of mine to ask that person to come to me and apologize. I’m gonna question what kind of white person who’s committed to anti-racism you really are if you have my phone number, you have all of my email addresses, you can DM me on Twitter and Facebook and Instagram and whatever else—literally, send me a carrier pigeon—and you choose not to. Yes, I am going to question your commitment to anti-racism.”

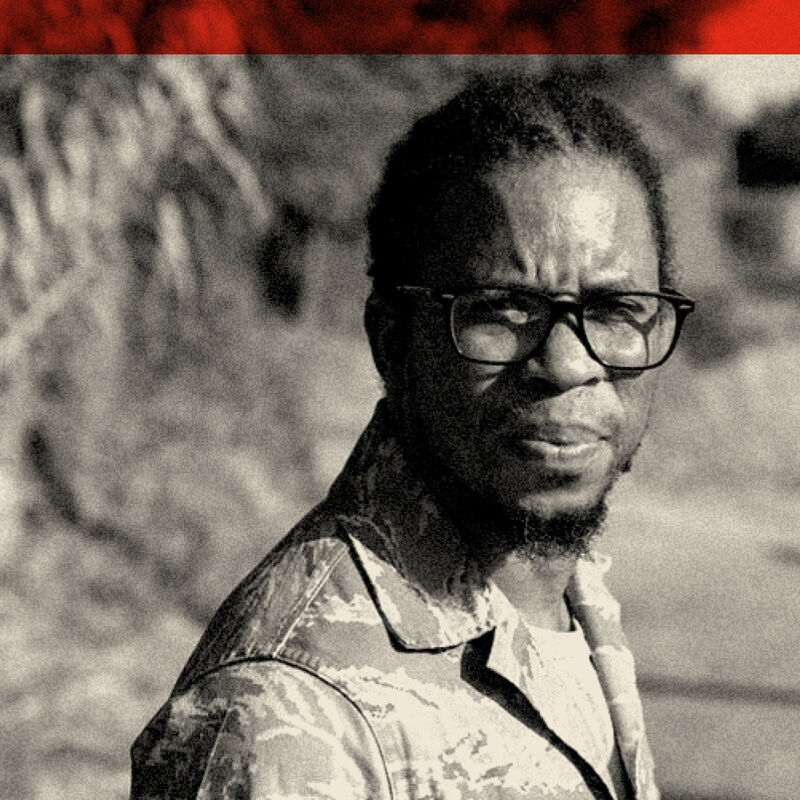

Theo Henderson

“George Floyd was the one that was videoed, and the shot was [seen] around the world. But an unhoused Black man—who is 40 percent of the population that is unhoused out here—is not seen. It’s not even talked about. That’s something I would like to see changed and understood as well.”

Dr. Steven McDonald

“We’re really not talking about race as explicitly as I think we need to be. We’re seeing the efforts from the Trump administration to suppress critical race theory are now sort of bleeding over into where we are currently.”

Ben Crump

“We’re not talking about environmental injustices enough. I represented thousands of citizens in Flint, Michigan, in the water lead-poisoning crisis. But there’s a Flint in every state in America. It’s just being ignored. In every state, Black people breathe more polluted air than anybody else because these chemical companies are allowed to exist within our community. Our children often have a third of the lung capacity, like in South Central Los Angeles, versus white children who moved 15 miles down the road in Santa Monica, California. We have to talk about this environmental racism.”

Sandy Hudson

“We don’t often talk enough about police and gender-based violence and how that gets carried out and what it looks like. There’s a way that women are used to justify the actions and continued support for police. Oftentimes, the first thing that I’ll get when I’m in a debate with someone is, ‘OK, what are you going to do when women are raped?’ And somehow we missed in this conversation that the police don’t take care of that at all anyway and that the police are perpetrators in that way. It’s really stunning that in our society this is such a pervasive issue, gender-based violence, whether that looks like sexual assault or domestic violence or the backlash against gender non-conforming people, and we really have nothing, zero services that are provided by our society to take care of that problem, to prevent it, to address the needs of survivors, besides community-based supports.”

Chris Wise

“People are talking a lot. I don’t think it’s necessarily a lack of volume but a lack of quality in conversations. People are talking about things like critical race theory or what police abolition actually means, as opposed to the common misconception that that just means, ‘I want to send all of the police into space.’ I don’t want to send them into space. I want to get rid of the system that is producing them and replace it with something that works. Police reform would be like, ‘Oh, add some salt and paprika to the fish and make it taste better.’ And police abolition is like, ‘Here, let me take this back to the kitchen. We’re going to make you a new one.’ And so it’s not taking it back. We’re just going to redefine what this is and how we do it, because what we have is not working.”

Tyrek Morris

“We aren’t talking enough about Black trans people. We talk a lot about cisgendered Black males, but we need to be talking more about intersectionality within Black lives.”

Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II

“It’s going to take more than training. It’s going to take laws. Dr. King once said, ‘A law may not make you love me, but it can keep you from lynching me.’ And I think even as we talk about passing the George Floyd bill, it has left me after the case saying there can be no compromise on that bill. In fact, we may need to go in and look at even how it needs to be stronger. Because if it took all of this just to get a conviction, I think about all the officers and the other cases where there was only insurance payments but no conviction. They’re still walking around free. Or how even in the Michael Slager case in South Carolina, it took the federal government convicting him because the state of South Carolina didn’t convict him even though he shot a man in the back, on camera, running away.”

Aisha Thomas

“We have to understand that when we deal with conversations of this nature, it’s not just about what’s happening in our minds, it’s also what’s happening in our bodies. It’s different for different people. When you have a child who may be fourth or fifth generation in this country, who may have had the legacy of slavery within their family trees that have a certain level of trauma, but there’s a different level of trauma for a child who may not have those descendants. Trauma can be passed on. I’m reading a really good book at the moment that talks about this in some detail, ‘My Grandmother’s Hands,’ by Resmaa Menakem. It really talks about racialized trauma and how we need to mend our hearts and our bodies.”

Ashley McGirt

“One of the biggest things that I’m extremely proud of is I started a nonprofit, the Washington Therapy Fund Foundation, which provides brief therapy to Black people. And we’ve been able to pay for several thousand therapy sessions for individuals. And the cool thing about it is therapists are paid an adequate rate. We normally have to discount our services or provide pro bono work to serve our community. But this is a way in which the community receives free therapy, and the therapists are paid, because it’s still a profession at the end of the day.

A lot of the donors have been white allies who have wanted to step up during this time and support the Black community. I’m always asked by white allies, ‘What can we do to help support the Black community?’ and I’m like, ‘Well, you can pay for our healing, you can pay for therapy.’”

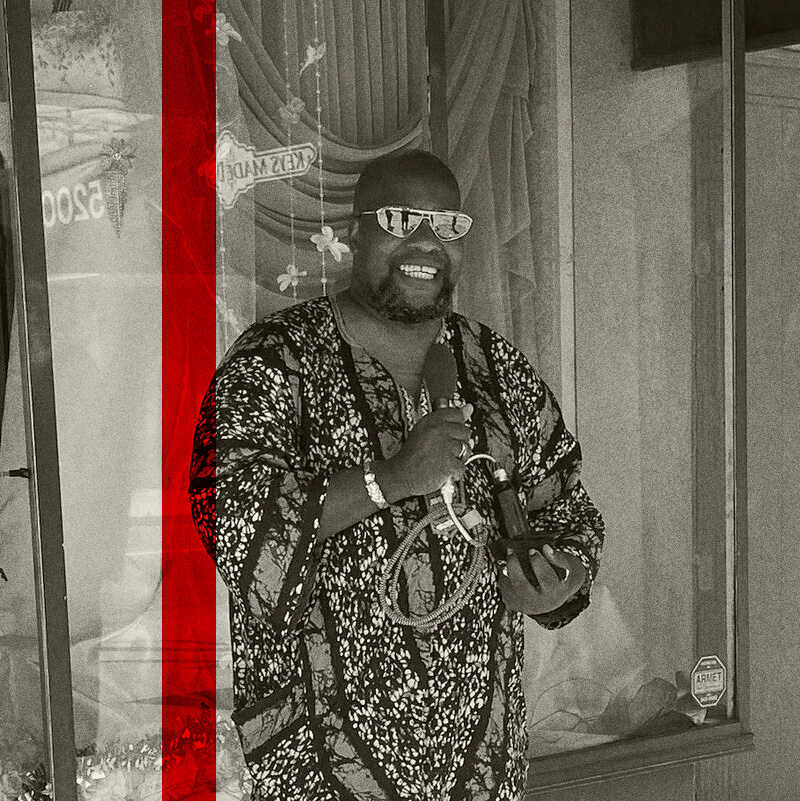

Yafeuh Balogun

“Last year, we were successful in changing Lamar Street, which Lamar was a Confederate leader in the state of Texas, to Botham Jean Boulevard. Dallas Police Headquarters is now on Botham Jean Boulevard. For us, Botham Jean is our local George Floyd.”

Rigodis Appling

“The City Council is deporting legislation that’s going to the state that requires new police officers to live in New York City. We all know that community policing works a lot better than having some officer from Long Island come. They live in their little white community in Long Island and they’re forced into the street of Bed-Stuy and they’re scared and they end up hurting people. If you’re going to have officers—which, again, I don’t think we need—but if you’re gonna have officers, then they should live in the community. That’s a direct way to make officers accountable. If your neighbor is an officer, you’re gonna know them and they’re gonna be more accountable.”

Shalini Kantayya

“I saw a sea change that I never thought possible when I began making this film. And that was that IBM said that they were getting out of the facial recognition game. Microsoft said they would not also sell facial recognition to law enforcement. And Amazon said that they would put a one-year pause on their sale to law enforcement—until June 2021.

And I think that really took place in part by the brave scientists who spoke out, who put their academic reputations on the line. Brave scientists like Dr. Timnit Gebru and Joy Buolamwini, who put their reputations on the line to show us the science that this tech has racial and gender bias. But also I think this change happened because of civic engagement and people taking the streets. All those companies made that change in June 2020 when they witnessed the largest movement for civil rights and equality that we’ve seen in 50 years around George Floyd. People started to draw the connections between Black communities being brutalized and by police and racially biased, invasive surveillance technologies like facial recognition and the potential harms they could do. And it’s my hope that the film ‘Coded Bias’ played a small role in making the public more literate about how AI technology works, and drawing the connections between the communities who are most vulnerable to its impacts.”

Bruno Sousa

“Without a doubt, our biggest accomplishment was the LabJaca project that we created in the middle of the pandemic in order to support and distribute food baskets and hygiene kits to people in our favela who couldn’t work or feed their families during lockdown. Aside from this, we started to monitor COVID-19 symptoms in partnership with a family clinic in the community. What we started to observe is that our data on COVID-19 symptoms was infinitely higher than the data that had been reported by the state. So what we realized was: the state isn’t going to produce sufficient data for the favela population that we all know is far more people than government figures reflect. How are there going to be vaccines for everyone if we don’t even know how many people are here?

From this, we created a clinic with data gathered from the whole favela and we offered virtual information about COVID-19 in graph and diagram formats so that all the residents can understand its meaning. The LabJaca project was my biggest professional achievement. It was the most structured and also won a human rights prize last year. We also received a message of support from our City Hall, so it’s a very powerful project with a lot of potential. The group is 100% Black. We started in the Jacarezinho favela but have since expanded to other favelas in the city.”

Gideon Oliver

“We got a settlement in a case that arose from a 2014 Black Lives Matter protest that resulted in NYPD policy change. The NYPD has these long-range acoustic devices [LRAD], which have two functions basically. One is like a glorified or extra-loud loudspeaker. And another is—I think now they’re calling it the warning tone, but they used to call it the alert tone or the deterrent tone. It’s a high-pitched noise that’s basically designed so that if you are in front of the LRAD and you’re exposed to this noise, it will be so painful that you have to move, or you can’t advance on the LRAD. You have to go away.

The police department, as a result of this settlement, has established a policy under which it has banned the deterrent tone. It will no longer use the deterrent tone, period, under any circumstances. Except the harbor unit can still use it in maritime situations.”

Carroll Fife

“The diverse voices around wanting something different. That’s very encouraging, that the calls for change are not just coming from activists. It’s just like a diverse choir of voices that are calling for the same thing. And especially white people, honestly. When white people got involved in the movements to help Black people vote in the South, like during the Freedom Summer, that’s when the government and different organizations were like, ‘Oh, fuck, now we got to do something about this stuff.’ The same thing happened around Black Lives Matter. And it’s unfortunate because we’ve been calling for freedom and the ability to move in the world—and the ability to just breathe—since we’ve been here, since we were brought here, since we were enslaved.”

Alan Duarte

“I think the only setback we have as Brazilians is political problems. We have a very ancient and old-fashioned political and bureaucratic system that hinders society’s progress and does not favor modernization. Some of our laws are centuries old and don’t relate to today’s world. Still, I’m very optimistic because the global population will encounter our proposal and hear our voice at any moment. Due to the internet, mothers and fathers cannot bring up their children the way that they were brought up. We’ll have to teach our children good practices on social media channels—so that there will be acceptance, understanding, and an exploration of content that will impact lots of people. Today it already does. Influencers with 30, 40, 50 million followers have the power to impact a lot of people. These people should have a commitment to share positive aspects for society.”

Tamara Toles O’Laughlin

“I’m optimistic about the collision of immigration and climate advocacy, for the sake of climate refugees, managed decline, and the ways racism underlies it all. I see folks outside of climate and environment moving into discussions about this, and it makes me hopeful.”

Rachel Bean

“I’ve felt some despair about how things have played out with the pandemic and promises to defund and abolish police that didn’t come to pass. People are worn down and tired by pandemic living. The presidential election and inauguration probably took years off our lives. So I feel exhaustion and doubt sometimes. But then I remember the energy of how we felt last April, May, and June, and I think, if it was possible then, it’s possible now. We, paraphrasing Adrienne Maree Brown, who was iterating from Octavia Butler, can shape change. We can create the future.

On April 15, 2021, I tweeted a question asking people if their position on policing had changed in the last year. One friend responded, "I went from ‘Abolition needs to happen’ to ‘Look at all the ways we’re already practicing it!’ and that’s really it. We’re already living in the future we’re trying to create and we’re already practicing abolition, mutual aid, and community care. That gave me so much hope.”